Re: Shoemaker & Reese’s piece about hierarchy of influences says that “Routines in which starting times and deadlines are followed also tend to create gaps in what news is covered, according to research. It would be interesting to see how 24-7 online news has affected this.” How do you think the constant interconnectivity and need to stay apprised on the latest happenings coupled with our American desire for instant gratification fuels 24/7 news sources? It’s a common journalism anecdote—the one the author described about being in a meeting and copying/adhering to (or at the very least, following) the NYT agenda. This happens a lot. But I worry that the pitfall with this is that news just becomes recycled and monotonous, and there’s nothing beyond the tiny scope of our locale, region, city, state, town, community, state, and nation. That is why “global” news sources are important—like Al Jazeera and BBC. No news source is perfect, but we should definitely be aware of what goes on beyond the limits and confines of our own immediate community. How can we get people to be more interested in “global” news outlets like BBC and Al Jazeera? What do you think are the pros and cons associated with “global” news sources like those?

Re: Keith’s “Shifting Circles” article – It says, “among online news media outlets, for example, there is no standard staffing or process for preparing news for the Web. Even within individual newsrooms, routines have changed so often that dozens of routines for producing, editing, posting, and overseeing Web content may have been used and abandoned since the mid-1990s. That very tumult around online content production, however, suggests that a topic that has received some scrutiny deserves more.” What difference do you think it would make if online media outlets developed a standardized way of creating, editing, disseminating and updating their sites? Do you think this is desirable, feasible, etc.? If so, how do you imagine it would work? It might be a good idea because it would give us some sense of security as readers that our news sources follow some sort of protocol at least.

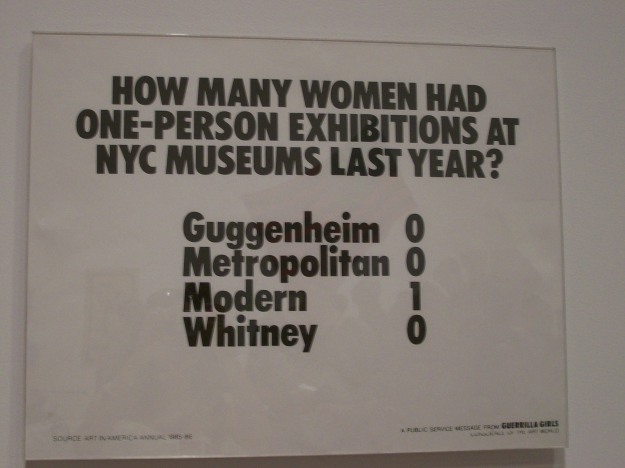

The anecdote about “Mr. Gates” to illustrate gatekeeping theory is still so true today. Editors have their own inherent experiences, opinions, views and biases – and even though they try to conceal or put aside those things, that doesn’t always work. After all, we saw that fact exemplified by something we read last class which said that despite NYT editor Jill Abramson being a female, men are still quoted a vast majority of the time in articles, especially about “female” issues like reproductive rights, pregnancy, contraception, abortion, etc. So she obviously has some biases and corporate influence that prevents her from publishing some things, and encourages her to publish some other things. Which leads me to my next question…. What is another way around the editor bias? Or is there even a solution to this? Wanting to know more about her as an editor (admittedly I didn’t know much), I began researching. Edward Bernays doesn’t begin any project without researching and so do I! J I found this pretty recent piece on her which I enjoyed reading – http://www.politico.com/story/2013/04/new-york-times-turbulence-90544_Page3.html. The article indicates that Abramson is uncaring and cold. On other days, Abramson seems disengaged from the newsroom. “When Jill is engaged, no one was better. She’s an incredible journalist,” one former staffer said. “But as often as not, she can be totally absent. There are days when she acts like she just doesn’t care.” I wonder how her attitude and lack of support and morale for her employees influences the content of the articles? I wonder what it would be like to work in such an environment. I am no stranger to having both good and bad editors, and it definitely makes a world of difference in terms of content, speed, accuracy, ethics, turnaround rate, and overall happiness or dissatisfaction level in the newsroom. It can influence your growth and training as a writer, too—especially if you’re relatively inexperienced. For many writers, journalism isn’t formalized in its protocol and process—it’s an exercise in heuristics. Learning habits from a good or bad editor can set up your outlook and opinions for many years to come, that’s why it’s so important to have a quality editor in your newsroom organization. What qualities do you think make up a “good” editor?

Re: Ch. 9 from the book – I found the crux of Schudson’s discussion about “who makes the news?” to be very interesting. Dr. Rodgers loves a good metaphor, and I thought the author’s metaphor about Michelangelo, David and marble to be a great analogy for expressing the power and influence journalists have—and differentiating between *real* and *perceived* influence. “It is common for social scientists who study news to speak of how journalists ‘construct the news’, ‘make news’ or ‘socially construct reality’ (p. 165). This point was a good counter to the claims made in the previous articles, especially the one by Shoemaker & Reese. Yes, there is a gatekeeper, but he (or she) is not as powerful and omniscient as we think. Referring to journalism as a tangible thing was a new concept for me, and I am sure it was for some of my classmates too. We are almost indoctrinated to view journalism as an abstract result of a particular situation—i.e., there was an earthquake and now this is a video clip/documentary/article/radio piece about that incident. It seems purely episodic to me. Schudson and Tuchman introduced a foreign concept to me in this chapter—that news can be a ‘depletable consumer product that must be made fresh daily’ (p. 165). Viewing it from that perspective made me more sympathetic toward news organizations and media outlets. They are competing like the rest of us—individually and as a group. Individual journalists are trying to get ahead, make a name for him/herself and establish social capital in the workplace. On a larger scale, the organization for which they work is also trying to do the same thing, while also competing with other rivals and corporate interests. It’s a delicate balance, and I honestly don’t think we give enough credit (or any, for that matter) to news organizations. Instead, we are so quick to villanize and blame them. Indeed, it’s also important to note the facts, that “there is no consistent support for the belief that independent news outlets offer more diverse content than those run by corporate conglomerates or that locally owned media are better for diversity than national chains” (p. 166). However, I really believe that piece of information would come as a huge shock to many people. It’s easy to criticize the media, and not so easy to think of ways to reform it. In that way, it is very similar to politics. According to the author, “it is the absence of commercial organizations, or their total domination by the state, that is the worst case scenario” (p. 166). In other words, censorship or total absence of autonomy is worse than corporate control of the media. I would agree with that. Many countries don’t enjoy the same level of “freedom” as we do (I put freedom in quotes because that’s a loaded term that means very different things to different people). But we have the First Amendment in this country—like it or not. It’s better to have a variety of news (level of quality is up for debate), but be awarded the choice to sift through information that is readily available and draw your own conclusions. Dr. Rodgers has a link on his blog to the most censored countries in the world, which is appropriate given the aforementioned topic: http://cpj.org/reports/2012/05/10-most-censored-countries.php. The country where my parents were born, Iran, ranks number four on this list. I already knew this, as I had the opportunity to interview Nobel Peace Prize winner Shirin Ebadi. In her speech, she discussed censorship and the need for democracy in Iran (picture below).

Re: the YouTube video interview with Dr. Schiller was interesting. His original background is in economics, but he shifted to communications after finding economics to be “too restrictive” in practice, teaching and how it is written. How do you think communications and economics are related? Different? I think that the corporate nature of both fields is important to be aware of. Schiller discusses this about 13 minutes into the video clip, calling it a “media monopoly.” Thus, it can be said that capitalism is not just the basis of our country’s economic system, but also infiltrates other fields such as communications and media. The interconnectivity cannot be overlooked.

DQs:

– How do you think the constant interconnectivity and need to stay apprised on the latest happenings coupled with our American desire for instant gratification fuels 24/7 news sources?

– How can we get people to be more interested in “global” news outlets like BBC and Al Jazeera? What do you think are the pros and cons associated with “global” news sources like those?

– What difference do you think it would make if online media outlets developed a standardized way of creating, editing, disseminating and updating their sites? Do you think this is desirable, feasible, etc.? If so, how do you imagine it would work?

– What is another way around the editor bias? Or is there even a solution to this?

– What qualities do you think make up a “good” editor?

– How do you think communications and economics are related? Different?

Nicki Karimipour; nickik1989@ufl.edu